The bank is teaming up with Bram Cohen’s San Francisco startup to prove that crypto can be part of the solution, not a problem, for climate change.

It was one of the most unusual agreements to come from the frenzy of climate activity at COP26 in Glasgow. A tiny blockchain crypto company with the odd name of Chia announced a partnership with the World Bank, one of the largest and most influential financial institutions on the planet. Under a non-exclusive, open-source and no-cost agreement, Chia is working with the Bank’s Climate Change Group to support the development of the world’s first “Climate Warehouse,” an ambitious effort toward establishing a global carbon marketplace. A few days later Chia made another announcement, signing an agreement with the government of Costa Rica, a nation known for its leadership in environmental conservation and sustainable development, to provide technical services in support of that country’s National Climate Change Metrics System.

Who the heck is Chia? It’s the brainchild of Bram Cohen, one of the early developers of decentralized, distributed ledgers that sit at the heart of blockchain technology. Cohen became a cult figure of sorts in the early 2000s when he created the BitTorrent communications protocol that enables users to distribute data and electronic files over the internet in a decentralized manner. In teenage speak, that means downloading bootleg music.

Almost twenty years later, crypto coins, or “tokenized assets,” and the blockchain ledger where they reside are a hugely controversial but perhaps revolutionary turn in the world’s financial assets. The total value of these fast-growing assets is now more than $3 trillion.

The World Bank is now hoping blockchain technology will offer an important solution to a critical climate problem. It hopes to prove it can serve as a key to helping fix one of the key flaws of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement — failure to create an effective global carbon trading market. The Environmental Defense Fund estimates 50 carbon markets operating under different jurisdictions across the globe. Among the best known is the EU Emissions Trading System. California’s Cap-and-Trade Program is linked with the Cap-and-Trade System of Québec. These systems all operate a little differently, but the common goal is to put a price on carbon emissions so that capital moves towards more sustainable projects.

But critics have lambasted the fragmented carbon markets as little more than greenwash platforms for companies to buy unreliable carbon “credits” to offset their continued high carbon polluting ways.

The challenge has been that the World Bank’s effort to create a credible, reliable carbon market has proven to be a huge technological challenge. “With such diverse and separated systems, it is difficult to have a clear picture of the overall market activity across countries and institutions,” says Chandra Shekhar Sinha, an adviser at the World Bank.

Their latest experiment is bold. The World Bank and Costa Rica believe Cohen and Chia’s climate-friendly crypto solution will solve the numbingly complex puzzle of developing a digital trading network trusted by governments, traders and financial institutions alike. Up to now, today’s traditional financial infrastructure has not been up to the task.

For Chia, it’s to prove that the nascent cryptocurrency market is ready for adoption by the world’s largest financial institutions as an invaluable element of their financial infrastructure. If successful, the project could vault the tiny startup into a leadership position in the next round of blockchain and crypto development. “Chia brings a sustainable set of new technologies,” says Gene Hoffman, president of Chia Network Inc. “It’s an upgrade from what’s out there.”

Planting the seed

Understanding why Chia may be a blockchain blockbuster requires a little explanation of how cryptocurrencies and blockchain work. Invented in 2009 by a person or group of people using the name Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin created a decentralized, highly secure process to transfer “stores of value” (Bitcoins) and transact through a decentralized peer-to-peer network via network nodes, or, the number of computer devices connected to a blockchain. Through cryptography and public distributed ledger systems, Bitcoin could be sent without a central bank or other administrators. The process is called “Proof of Work (PoW).”

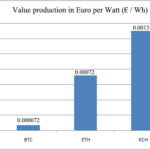

Today the mining of Bitcoin is said to use the equivalent of 28 Hoover dams, or 0.5 % of all electricity used globally, and seven times Google’s total usage.

Bitcoin’s “proof of work” protocols triggered the ongoing crypto craze — but caused a litany of issues as well. As the price of a Bitcoin soared, crypto miners started using gargantuan amounts of computer processing power –– and energy –– to validate and create new coins. Today the mining of Bitcoin is said to use 20% of the world’s base power or the equivalent of 28 Hoover dams. And because its distribution is untraceable, Bitcoin has become the currency of choice for tax dodgers, criminal syndicates and rogue nations like North Korea and Iran.

Enter Ethereum and Crypto 2.0. As the second-largest blockchain network, Ethereum is also built on energy-sucking PoW protocols, though it is now switching to a less power-consuming process called “Proof of Stake (PoS).” But to do so, the Ethereum-based network will be less secure because it relies on fewer nodes of computer operators. In the democratized world of crypto, the more nodes the better, because operators of the nodes vote on all of the business and governance issues of the network. For example, Bitcoin has at any one time up to 15,000 nodes. However, with Ethereum’s new “POS” protocol that number drops to as low as 2,400. This increases the chances that some organizations could hack into the Ethereum network and take it over.

Welcome to “Crypto 3.0”

Cohen and Chia say they have overcome all these issues by completely re-engineering the blockchain and crypto process to make it more secure, and consume less energy. It does this by using a process called Proof of Space and Time which relies on a computer’s storage space instead of energy-intensive computational computer power logs. If it takes 28 Hoover dams to power Bitcoin, it takes less than one Hoover dam to power the entire Chia network, or about the equivalent power needs of a large financial institution.

To reinforce its green image, and differentiate it from its crypto competitors, Chia calls its networking process “farming” rather than mining. Chia farmers “seed” their hard drives or solid-state drives with software that puts blockchain data into specific “plots.” Chia’s programming language, Chialisp, makes it possible to write smart contracts and build applications, similar to the way the Ethereum platform functions.

As important to its green credentials, are what it hopes will be its credibility with the world’s largest institutions. Unlike Bitcoin, Chia was not invented by a bunch of digital cowboys eager to beat the system, as an illicit work around traditional finance. Quite the opposite: It is designed to meet and complement traditional compliance and regulatory standards of large financial institutions.

It is Chia’s transparency, integrity and security that appear to make it a perfect fit for the World Bank’s Climate Warehouse, says Susan Carevic, IT business management officer at the World Bank’s Climate Change Group. The Bank’s Climate Warehouse needs a network of transparent, traceable data so others can create a credible carbon market, she says. This allows the Climate Warehouse to create a public good, data layer that sits atop a blockchain which would mean no single country would own the blockchain but each participating entity would have access to its data. “Interoperability is built into it,” says Shekhar Sinha.

This is crucial because any successful carbon market must connect hundreds of government climate registry systems that have key data needed to verify if a carbon credit is really helping mitigate climate and then make that data available to trade carbon credits.

It takes less than one Hoover dam to power the entire Chia network.

For Chia, it’s a golden opportunity to showcase its climate-friendly blockchain network. Neil Cohn, Chia’s global head of markets and sustainability, said it was bold of the World Bank to take a chance on Chia rather than more established networked cloud giants like Microsoft, Amazon or Google.

Even before the World Bank announcement, Chia had been receiving a lot of interest in Silicon Valley. In May, it raised $61 million in Series D funding to give the company an estimated $500 million valuation. Venture capital giants Andreessen Horowitz and Richmond Global Ventures led the funding round that also included Breyer Capital, Slow Ventures, True Ventures, Cygni Capital, Naval Ravikant, Collab+Currency, and DHVC.

But the impact of a successful World Bank blockchain project may reverberate far beyond carbon markets. If blockchain technologies like Chia’s can overcome the environmental, security and governance questions, it will become the “financial rails of the new economy,” says David Frazee of Richmond Global Ventures and a Chia board member. It will be the blockchain-driven internet of markets that will be “moving trillions of dollars in the world’s financial and economic sectors,” he says.

Growth pains

But critics of Chia’s methods are already starting to sprout. Last spring, prospective Chia farmers created so much demand for computer hard drives that it caused shortages and price spikes. Critics also blame Chia farming for shortening the endurance of some consumer SSDs, causing more e-waste rather than reducing it. Responding to critics, Cohn says more than 70% of hard drives go to data centers that replace them every three to five years with newer, larger-capacity drives. At present, the older hard drives get physically shredded and end up in landfills. With Chia, they could be securely reused.

The stakes for the World Bank, Chia and financial institutions are huge. If a climate-friendly blockchain can be developed that also overcomes nagging security concerns, it could not just fix broken carbon markets, but become a catalyst “transforming the global economy,” says Cohn.

It may also open the doors to what has been up to now a very exclusive club of bankers, investors and financiers. Blockchain’s efficient and decentralized nature may be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to democratize finance, promote inclusive prosperity and give everyone a seat at a more diverse and inclusive financial table.

That dream seems a far cry from the wild and wacky world of today’s crypto madness, where a digital drawing of a gorilla can sell for millions, sports stars demand their salaries in crypto coins, and where a single tweet from Tesla founder Elon Musk can rock volatile trading markets.

Chia and the World Bank are out to prove there is more to crypto than hype.

Written by

Jim Gold

Jim Gold is a California-based reporter and editor who has covered business, personal finance, water and environmental issues. He was a senior editor at MSNBC.com and Phoenix-based The Arizona Republic newspaper. His earlier daily newspaper experience includes editor-in-chief of The Stockton Record and assistant managing editor of the Reno Gazette-Journal.

Source: https://www.climateandcapitalmedia.com/the-world-bank-plants-a-seed-to-solve-climate-change/